Mosasaurs, Sharks, and Other Marine Creatures from the Cooperstown Pierre Shale Siteby |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

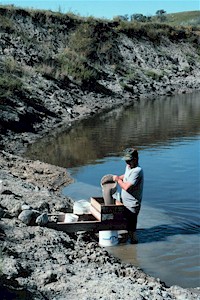

Screen

washing of the fossiliferous claystones of the Gregory Member

has yielded an extensive array of invertebrate fossils of

creatures that inhabited the Pierre Sea (Figure 3 ). This fauna

includes foraminifera (one celled organisms that secrete minute

shells), bryozoa (lace animals -- Figure 4A), brachiopods (Lingula --

Figure 4Bcorals (Micrabacia --

Figure 4C and others -- Figure 4D ), scaphopods (tusk shells),

clams (Inoceramus, Nucula --

Figure 4E , Nuculana, Pteria,Nemodon?

-- Figure 4F , oysters, and many others), snails (Margaritella --

Figure 4G, Trachytriton --

Figure 4H , Atira,Oligoptycha, Graphidula?,

and many others' -- Figure 4I, cephalopods (Baculites

gregoryensis --

Figure 4J & 4K,Didymoceras --

Figure 4L , Solenoceras

mortoni -- Figure

4M), annelids (worm tubes), crustaceans (the crabDakoticancer,

the lobster Hoploparia,

the shrimp Callianassa--

Figure 4N , and the tiny bivalved crustaceans called

ostracodes), star fish -- Figure 4O , and sea urchins (Eurysalenia --

Figure 4P & 4Q). The Cooperstown site is the only place in North

Dakota where many of these kinds of fossils are found although

similar fossil faunas have been recovered in South Dakota and

Wyoming. These fossils suggest that the Pierre Sea, in the

Cooperstown area 75 million years ago, was shallow and warm. The

cephalopods indicate that the Gregory Member at the Cooperstown

site is middle Campanian in age. That is, these rocks (including

the fossil shells) were deposited on the floor of the Pierre

Sea about 75 million years ago (Figure 5).

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

Several

kinds of interesting fossils of vertebrate animals are found in

the lower part of the DeGrey Member, just above the fossil bed

containing the invertebrate fossils. These fossils provide

information about the kinds of vertebrate animals that inhabited

the Pierre Sea. Included are the teeth of several different

kinds of sharks such as Squalicorax (extinct

cow shark -- Figure 6A), Pseudocorax (another

extinct cow shark -- Figure 6B), Cretolamna(Figure

6C ), Carcharias (sand-tiger

shark -- Figure 6D, and Squalus (dogfish

shark -- Figures 6E & 6F ). The remains of bony fish are also

present in the DeGrey, including the teeth of the salmonlike Enchodus (Figure

6G). A tarso-metatarsal bone of the

hesperornithid bird Hesperornis was

also found in this interval (Figures 6H & 6I).Hesperornis was

a large, up to about two meters tall, flightless seabird. This bird was equipped with

sharp, pointed teeth and probably preyed on fast-moving fish and

squids underwater. Although this bird was incapable of flight,

it was a swift swimmer that propelled itself through the

shallow, coastal waters of the Pierre Sea with its powerful hind

legs similar to the modern loon. Coprolites, fossilized

excrement, are trace fossils found at the site (Figure 6J).

These fish and birds existed with the large marine reptiles, the

mosasaurs, that inhabited the Pierre Sea.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| The remains of twelve mosasaurs have been found in the lower part of the DeGrey Member from an area of about one-square kilometer at the Cooperstown site. Fossils of two kinds of mosasaurs, Plioplatecarpus and an unidentified mosasaurine, are present. Mosasaurs were marine lizards that inhabited tropical to subtropical oceans, like the Pierre Sea, in coastal areas with water depths of probably less than 100 fathoms (90 meters) during the last part of the Cretaceous Period (Western Interior Seaway Painting). They, like the last of the dinosaurs, became extinct at the end of the Cretaceous, about 65 million years ago. Although they were large reptiles, and lived at the same time as dinosaurs, they were not dinosaurs and were most closely related to the living varanid (monitor) lizards (e.g., Komodo dragon of Indonesia). Like many dinosaurs, however, many mosasaurs were huge animals with long lizard-like bodies attaining lengths in excess of 7.5 meters (Figure 7A). Unlike their terrestrial lizard relatives, the limbs of mosasaurs were modified to form flippers. Mosasaurs swam by lateral undulations of the posterior part of their elongate bodies and laterally compressed tails. Their flippers were used primarily for steering rather than for propulsion as the animal glided through the water. The shape of the skeleton of Plioplatecarpus suggests that it was probably a slow but agile swimmer, similar to the living seal. Mosasaurs were active carnivores and among the main predators in the Pierre Sea as attested to by their large jaws studded with sharp, conical teeth (Figures 7B &7C). They probably preyed on other mosasaurs, fish, turtles, cephalopods and other invertebrates. It has been suggested that mosasaurs relied on highly developed senses of sight and smell to locate and catch their prey. | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

Until last

fall, the only mosasaur remains found at the Cooperstown site

were isolated vertebrae, teeth, other small skeletal parts.

While exploring the far western portion of the Pierre outcrop

area at the site, Mike and Dennis discovered a

eight-centimeter-long section of mosasaur jaw, with teeth,

beginning to weather out of the Pierre Shale on a small hill

(Figure 8). Johnathan Campbell (the Survey's fossil preparator)

and I traveled to Cooperstown expecting to spend 2 or 3 hours at

the site extracting the jaw from the rock. Four days later we

were still there excavating what was beginning to emerge as a

fairly complete mosasaur skeleton. We had to terminate the dig

because of bad weather, but returned to the site this July to

complete the excavation. As expected, most of the skeleton was

preserved, the most complete mosasaur skeleton ever found in

North Dakota. It is difficult to determine at this point exactly

how complete the skeleton is because the bones were removed in

two very large and several smaller plaster field packages

(blocks of rocks containing the fossil bones are encased in

plaster casts before removal to help preserve the fragile bones

-- Figures 9-12 ). The lower jaws with teeth (Figure 7B),

disarticulated skull, first 20 vertebrae (articulated), shoulder

blades (Figure 7D), coracoids, and front and back flipper

elements are present and many other bones are hidden in the

field packages. Preservation of the bones is excellent allowing

us to identify the skeleton as a six- to eight- meter-long

specimen of the mosasaur called Plioplatecarpus.

We have begun preparation and study of the fossils from this important Pierre Shale site and have presented some preliminary results of our findings (Figure 13 and see additional readings below). These fossils provide a glimpse of what life was like in the shallow, subtropical sea that covered the Cooperstown area. It was obviously teaming with life reflected by the variety of fossils found at the site. We expect to learn more as work continues on the fossils. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

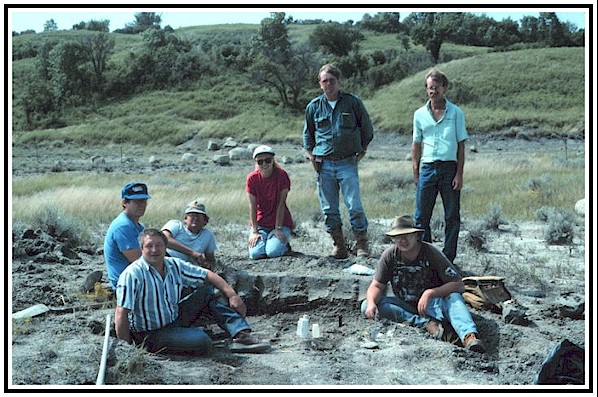

One of the intriguing questions is how the mosasaurs at this site may have died. Is it possible that these animals all died at about the same time, suffocated by volcanic ash? The mosasaur bones are found in the Pierre Shale associated with layers of bentonite, altered volcanic ash. Did volcanic eruptions far to the west create enough air fall ash in North Dakota to decimate the mosasaur population in the Pierre Sea? We are also interested in how these animals interacted as a community. During preliminary cleaning of some of the mosasaur bones, teeth (Figure 6E ) and placoid scales (Figure 6F) of dogfish sharks were found with the mosasaur bones. Sharks often loose their teeth while feeding. Could it be that dogfish sharks scavenged this mosasaur carcass? Or, perhaps the mosasaur preyed on the dogfish sharks and these teeth and scales are undigested residues. Hopefully we will be able to answer some of these questions. Mike,

Dennis, Verla, and I would like to thank Orville and Beverly

Tranby and family and the Tim Soma family for allowing us to

collect and study fossils from their property (Figure 14). These

fossils are currently in our laboratory at the North Dakota

Heritage Center in Bismarck for curation and study. Most of the

fossils, however, will eventually be exhibited at the Griggs

County Museum in Cooperstown. We believe that the Plioplatecarpus mosasaur

skeleton is complete enough to restore as a three dimensional

skeletal mount exhibit. Because of the importance of this

specimen, Orville and Beverly and Beverly's sisters, Mrs. Gloria

Thompson, Mrs. Jacqueline Evenson, and Mrs. Susan Wilhelm have

decided to donate this fossil to the North Dakota State Fossil

Collection for study and exhibit at the Heritage Center.

We thank them forthis donation as it will be an educational and

a popular exhibit that will be viewed by many. Chris Dill, State

Historical Society of North Dakota and Museum Director of the

Heritage Center, enthusiastically supports a mosasaur exhibit

and has given us the authorization to proceed with the

exhibit plans. A fossil restoration project such as this

is a major and expensive undertaking and will be accomplished

only through private donations. If any of you are interesting in

financially supporting the restoration of the Cooperstown

mosasaur for exhibit at the Heritage Center please contact me.

ADDITIONAL READING

Hoganson, J. W., Hanson, Michael, Halvorson, D. L., and Halvorson, Verla, 1996, Stratigraphy and paleontology of the Pierre Shale (Campanian), Cooperstown site, Griggs County, North Dakota: Proceedings of the North Dakota Academy of Science, v. 50, p. 34. Hoganson, J. W., Hanson, Michael, Halvorson, D. L., and Halvorson, Verla, 1996, Mosasaur remains and associated fossils from the DeGrey Member (Campanian) of the Pierre Shale, Cooperstown site, Griggs County, east central North Dakota: Geological Society of America, Rocky Mountain Section, abstracts with programs, v. 28, no. 4, p. 11-12.; |

||||||||||||||||||||||

Figure

14. Mike Hanson,

Dennis Halvorson, Gene Loge, Beverly Tranby, Orville Tranby,

Johnathan Campbell, and Scott Tranby at the mosasaur excavation site. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

6I.

Tarso-metatarsal of a

6I.

Tarso-metatarsal of a